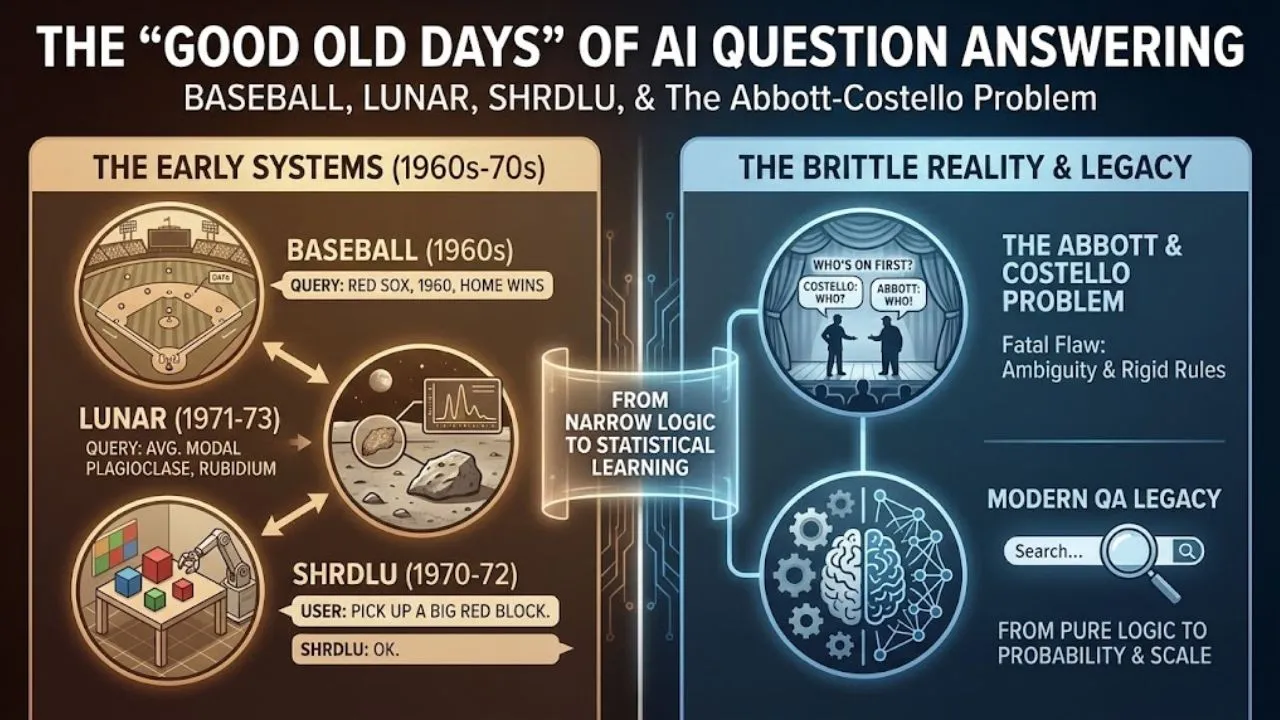

Long before large language models could answer almost any question with near-human fluency, question-answering (QA) systems were narrow, rule-based, and domain-specific. In the 1960s and early 1970s — the golden age of symbolic AI — researchers built impressive but brittle natural-language interfaces to structured knowledge. These systems worked beautifully within their tiny worlds… and failed spectacularly outside them.

Today we look back at three landmark systems that defined early QA: BASEBALL (1960s), LUNAR (1970s), and SHRDLU (1970–1972). Their story is also the story of why modern QA had to abandon pure logic and embrace probability, scale, and messiness.

1. BASEBALL (Green et al., MIT, late 1960s)

The very first domain-specific QA system people usually point to was built around… American baseball statistics.

How it worked

- Input: Questions in restricted English about a fixed database of one season’s games (teams, scores, players, locations, dates, etc.). Examples: “Which teams won games in July played at home?” “How many games did the Red Sox win in Boston in 1960?”

- Core technique:

- Each word was matched to a database field (team name → TEAM, win → RESULT = WIN, July → MONTH = 7).

- The system built an implicit SQL-like query: SELECT COUNT(*) FROM games WHERE team = ‘Red Sox’ AND location = ‘Boston’ AND month = 7 AND result = ‘win’.

- No deep syntax tree — just keyword-to-field mapping + simple conjunctions.

Strengths & limits It was elegant and reliable inside its sandbox. But change one word (“Did the Yankees beat the Red Sox?” → now you need negation, comparison operators, temporal reasoning) and it broke. No ambiguity handling, no world knowledge beyond the table.

Still: this was one of the earliest demonstrations that natural language could (in theory) replace formal query languages.

Read Also: AI Built Its Own Society: 7 Powerful AI Updates That Changed Everything This Week

2. LUNAR (Woods et al., BBN, 1971–1973)

LUNAR took QA to the next level — and to the Moon.

Domain: The Apollo lunar rock samples database (chemical composition, mineral content, sample location on the Moon, etc.).

Capabilities It answered far more complex questions than BASEBALL, including aggregates and filtering:

- “What is the average modal plagioclase concentration for lunar samples that contain rubidium?”

- “Which elements occur in highland samples but not in mare samples?”

Technical innovations

- Full syntactic parsing using a context-free grammar + augmented transition networks (ATNs).

- Semantic interpretation → converted parse tree into a formal logical query (a precursor to lambda calculus / FOL representations).

- Executed against a structured database.

- Early form of “information retrieval” — retrieved relevant documents/topics before full analysis (though rule-based, not statistical tf-idf).

LUNAR handled relative clauses, quantification (“all”, “some”, “average”), comparison, and negation — a huge leap from keyword matching.

Limits Still extremely brittle. One misspelling, unusual phrasing, or question outside lunar geology → failure. No learning, no generalization.

3. SHRDLU (Terry Winograd, MIT, 1970–1972)

SHRDLU is the most famous — and philosophically richest — of the early QA systems.

Domain: A simulated 3D “block world” of colored blocks, pyramids, boxes sitting on a table. The user could ask questions and give commands to manipulate the world.

Famous examples:

- “Pick up a big red block.”

- “Which cube is sitting on the table?”

- “Put the blue pyramid on top of the green cube.”

- “Why did you move the green block?” (explanation of reasoning)

Key breakthroughs

- Dynamic world model — the knowledge base changed as the user issued commands.

- Reference resolution & clarification — if ambiguous (“the red one” — which red?), SHRDLU asked clarifying questions: “Do you mean the small red cube or the large red pyramid?”

- Deep semantic parsing → sentences → logical form → planner → world update.

- Natural language generation — could explain its own actions (“I moved the red block because you asked me to stack it on the blue one”).

- Integrated vision (simulated), planning, and dialogue in one system.

The name “SHRDLU” A deliberate nod to the fallibility of technology. In old Linotype printing machines, operators typed “ETAOIN SHRDLU” (the two most common letter columns on the keyboard) to mark a line as garbage when they made a mistake — because there was no backspace on molten metal slugs. SHRDLU became a symbol of “garbage in, garbage out” and the limits of mechanical understanding.

Winograd chose the name ironically: his system was trying to create a coherent “reality” from text input — exactly what a Linotype operator hoped to avoid producing.

The Abbott & Costello Problem: Why Early Systems Were Brittle

The classic “Who’s on First?” routine illustrates the fatal flaw of these systems:

- Costello keeps interpreting “Who” as the question word (“who?”).

- Abbott means the literal player name: “Who” (the guy on first base).

Pure rule-based parsers always treat “who” as interrogative — they have no way to flip it to a proper noun without massive context or statistical priors. Natural language is full of such ambiguities:

- Proper nouns vs. question words

- Anaphora (“it”, “the one”)

- Metaphor, sarcasm, idioms

- World knowledge gaps

These systems were perfect in toy worlds but collapsed in the real one.

Read Also: The Dawn of AI: From the 1950s Optimism to the Birth of Thinking Machines

Legacy & Transition to Modern QA

By the late 1970s, the limits were clear:

- Hand-crafted rules scale poorly.

- Ambiguity and open-domain questions kill brittle parsers.

- The world is too big to encode everything symbolically.

The field shifted:

- 1980s–1990s: expert systems & knowledge bases (still symbolic, still narrow).

- 2000s: statistical methods (IR + machine learning).

- 2010s: deep learning + large-scale retrieval (Watson, DrQA).

- 2020s: end-to-end neural QA + massive pre-trained models.

Yet echoes remain: semantic parsing lives on in things like semantic role labeling, logical form induction in neuro-symbolic AI, and even parts of tool-calling in modern LLMs.

The “good old days” weren’t perfect — they were narrow, slow, and unforgiving. But they proved something profound: language could be turned into executable meaning, worlds could be built from sentences, and machines could ask clarifying questions when confused.

That spirit — and those hard-learned lessons about ambiguity — still shape every question we ask an AI today.

Disclaimer: This article is based on historical descriptions of BASEBALL (Green et al., 1960s), LUNAR (Woods, 1973), and SHRDLU (Winograd, 1972), drawn from original papers, Winograd’s thesis, and standard AI history references (e.g., Speech Understanding Systems, Understanding Natural Language, Russell & Norvig). Technical details reflect consensus accounts as of 2026.